<iframe width="420" height="315" src="http://www.youtube.com/embed/ocwTHbYXqng" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Inheriting injustice: A chilling film on India's Dalits

Mumbai: "Every day two Dalits are raped and three killed," goes a shocking statistic in well-known filmmaker Anand Patwardhan's latest documentary, "Jai Bhim, Comrade".

It begins with such murderous day, July 11, 1997, when 10 Dalits gathered to protest the desecration of an Ambedkar statue were shot dead by Mumbai Police. Six days after this massacre, unable to take the pain and grief of his people and as a mark of protest, Dalit singer, poet and activist Vilas Ghogre committed suicide.

"Jai Bhim..." then traces the legacy of the unique democratic protest style of the Dalits through their stirring poetry and music and the story of Ghogre and other singers and poets.

What emerges are tales of injustice and atrocities in the world's largest democracy that will wrench your gut. Its riveting parallels span not just Maharashtra (where the film is situated) but the world.

A Dalit leader in the film is heard saying, "We have a singer, a poet in every home." It is here that you realise the similarity between the fight for justice of the mostly lowly and oppressed of Indian people with that of Afro-Americans. Both share a strong tradition of music and poetry that provides them relief, strength and prepares them to fight against injustice.

This is the reason why the state of Maharashtra blacklisted one of the strongest Dalit music groups (prominently featured in the film), the Kabir Kala Manch (KKM), by calling them Maoists.

Patwardhan has a keen sense of social satire. He rips apart the notion that equal justice prevails for everyone in India. When you see political leaders of national stature speaking of wiping out entire castes and religions, which in a true democracy would have landed them in jail, you realise how truth can sneak out from rhetoric and rewriting of histories, and punch you in the gut.

Documentaries thus serve as a public justice system. The powerful may not be punished for their murders, but those who see the film can see their true face, and remember.

'Jai Bhim...' also abounds in irony of how a constitution drafted by a 'dalit', Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, continues to fail his own community. It balances the grand sweep of dalit injustice with individual stories. Thus on one side you see a Dalit working in a garbage heap without the basic protection, cleaning Mumbai's filth, you also see middle-class Mumbai talk about 'how dirty and filthy these people are.'

The film's objectivity is laid bare because it spares no one. Speaking to IANS, Patwardhan said, "The film is critical of everything, even the Dalit movement, except its youth who have been forced to go underground."

In a fitting screening, which Anand calls its 'real' premiere (previously screened in a few film festivals), over 800 people in BIT chawl in Byculla, where a part of the film was shot, sat mesmerised Monday, without a break for its 200-minute duration.

In an ideal world, cries against Dalit injustice would have sprung all over. Since we don't live on a just planet, "Jai Bhim, Comrade" will retain relevance so long as caste-based atrocities are not uprooted.

For it may have taken Patwardhan 14 years, in reality this story of those who inherit injustice in their geneshas been in the making for thousands of years in India.

Jai Bhim Comrade: Where The Republic Still Lives

February 2, 2012http://moonchasing.wordpress.com/2012/02/02/jai-bhim-comrade-where-the-republic-still-lives/Jai Bhim Comrade: Where The Republic Still Lives

February 2, 2012

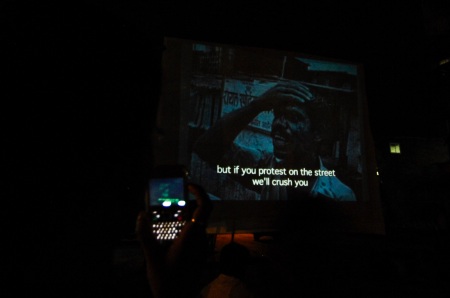

A teenage boy records a scene from documentary film Jai Bhim Comrade that was shown on the 25th of January, 2012, at Ramabai Nagar, where on the 11th of July, 1997, 11 people were killed in police firing.

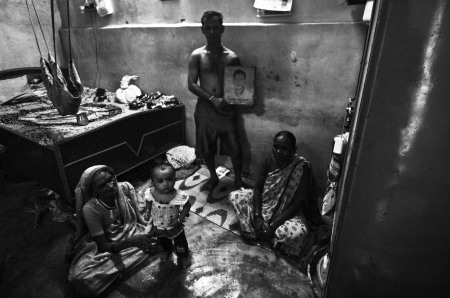

The family of Namdeo Surwade who died of his injuries a few years after the firing.

Early on the morning of 11th July, 1997 at the Ramabai Nagar in Ghatkopar, Mumbai, a woman saw a garland of slippers on the statue of iconic leader B.R. Ambedkar. Within a few hours angry Dalits had gathered on the highway to protest against the desecration.

By 7:30 am, a police van would stop 450 meters away from the protesters, disembark and immediately start firing. They'd fire over 50 rounds within twenty minutes into small lanes and by-ways and into people's homes – into the homes of people who were not even protesting.

They killed ten people.

Young Mangesh Shivsharan was shot in his head, right in front of Namdeo Surwade who was shot on his shoulder.

'The boy's brains were all over my father' said Manoj about his father Namdeo Surwade, a handcart puller who could never work a day after the injury and died a few years later, becoming the eleventh victim.

But there was another casualty of the killings at Ramabai Nagar.

Vilas Ghogre, Dalit poet and singer, committed suicide horrified by what he saw at Ramabai and the realization 'that this country is not worth fighting for anymore' as witnessed by his friend, singer Sambhaji Bhagat in Anand Patwardhan's new film Jai Bhim Comrade, screened at Ramabai Nagar on the eve of the nation's 63rd year as a Republic.

For three and a half hours, over fifteen hundred people saw the film on a makeshift screen, many standing through its entire duration. The film details not just the life of Vilas Ghogre and the police firing but its aftermath – the movement for justice that led to the police officer who ordered the firing to spend less than a week in 'hospital' (not jail), before being let off on bail by the High Court. It tells other stories – the martyrdom of a young Dalit Panther Bhagwat Jadhav, killed by the Shiv Sena at a protest rally in 1974; the incisive and fiery oratory of Panther leader Bhai Sangare that possibly led to his martyrdom in 1999; the Khairlanji massacre and continuing atrocities in the countryside. It examines the assault on the Constitution and the slow appropriation of radical Dalit leaders into mainstream Congress or hardcore rightwing politics while also critically examining the role of the left in dealing with caste.

Highlighting precarious livelihoods, it paints intimate family portraits of ordinary Dalits across Mumbai and Maharashtra and all this intersects seamlessly with the central role of music in not just the film but in the Dalit politics of resistance. Protest songs sung in every chawl, basti and galli lead us to the newest generation of cultural activists/musicians such as the Kabir Kala Manch, whose songs are viewed as such a threat by the State, that they're branded as Naxalites and forced to go underground.

The religious mother of the enigmatic singer Sheetal Sathe of the Kabir Kala Manch, would say, 'At every performance my children always assured me that they'd never take up arms, that they'd change the world only through song and drum.'

Yet cultural and social revolution is a threat in the same country where freedom of speech and expression is a privilege.

At Ramabai, young teenagers with moist eyes watched the screen quietly, listening to a spirited widow describe how her husband's hands were slashed by upper caste men, and how he bled to death while the police refused to take their statement. The proud woman had saved Rs.5 and Rs.10 a day over the years to buy herself land and educate her children. When the filmmaker asks her how she kept up her spirit, she replies: 'I can't afford to lose. What'll happen to my children if I lose?'

When a group of boys were asked what was their favourite part of the three and a half hour film, they replied, in unison: 'The songs of the Kabir Kala Manch.'

No wonder the state views them as a threat. Resistance and symbols of resistance need to be wiped out like Pochiram Kamble who was killed for uttering the words 'Jai Bhim'. Yet the film that documents the recent decades of caste oppression and it's growing denial, has found that symbols of joy, hope, perseverance and resistance, always survive, irrespective of thousands of years of oppression.

Another Dalit leader Ashok Saraswat's speech in the film drew laughter from the crowd at Ramabai: 'Unfortunately we gave up 330 million gods but made Ambedkar into a god. We wear Babasaheb Ambedkar's photo around our neck. On waking up, we say "Jai Bhim". Before sleeping, it's "Jai Bhim" and when having a little drink, it's Jai Bhim!"

"Listen people! God is not in temples or idols. God is found through service to the poor. Gadge Baba would ask – 'Is Ganapati a god ?'

'Yes, Baba!'

'Who made Ganapati?'

'A potter did.'

'So tell me who is Ganapati's father?'

'The crowd wouldn't answer.'

'Ashamed to say it?'

"Then softly they'd say: 'Ganapati's father is the potter.'"

The crowd of Ramabai, especially the young, laughed out loud but none of them found the scenes of puerile racism from the middle and upper middle classes very funny.

The filmmaker interviews a young student from Jai Hind college who says, 'Dalit issue frankly is definitely ameliorated over the past half a decade or so.' A sentiment that is not only echoed in the mainstream media that is beginning to cite Dalit neo-liberalism as a way forward, yet those comments are put in sharp contrast to the National Crime Records Bureau that mentions 'Every day three Dalits are raped and two killed' and the conviction rate under the Prevention of Atrocity Act is a mere 1%.

In Beed district of Maharashtra, a young woman was raped by upper caste men, and her entire family was beaten for confronting the attackers. An old man from the same family begins to speak: 'We are responsible for this. We never got organized or converted to another religion. We failed to do that. Had we done it we could have mentally discarded caste and made others understand we are humans. We Mangs bear the brunt of injustice.'

'But those who converted to Buddhism also face atrocities.' says the filmmaker.

'Yes in some places it happens even to Buddhists. But they have the strength to retaliate. We lack that strength. That's the point.'

At that point, the crowd at Ramabai Nagar, was moved to cheers and applause.

No comments:

Post a Comment